|

|

Fullness of Absence: Nguyễn Thái Tuấn

|

|

|

Memories are motionless, and the more securely they are fixed in space, the sounder they are. ’

“The House, from Cellar to Garret. the Significance of the Hut”

in The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard, p.9

Untitled, from Heritage series. 2012. Oil on canvas. 170x150cm.

Primo Marella Gallery, Milan. (Fig. #1)

A heavily draped, dimly lit room of red-carpeted wealth is barely discernable as the eye feels the glare of daylight pulsating through the only window in the painting ‘Untitled’ (see Fig. #1) by artist Nguyễn Thái Tuấn. The beam of light focuses on a solitary upholstered chair that sits empty in the centre of the painting. The eye is drawn to a stuffed panther that sits above a wooden chest, its jaws open in a frozen snarl and then we realize that the back-turned figure in the room, dressed in an over-sized business suit and slippers, possesses no character, no head, no hands. This is Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s signature motif – the bodiless human figure – a pictorial ploy that questions human value in the face of political power, greed and social neglect. In this painting, we stand in the office of the President of the former Southern Vietnamese government and the man is a former leader of Northern Vietnam. The chair, the central focus of the painting, is left deliberately empty in the shadows as if the power of the country is left in question, like a symbolic borderline of two opposing forces reflecting the democratic South with the Communist North prior 1975 and the establishment of the Vietnamese Communist government. This painting is part of a series entitled ‘Heritage’ aligning Vietnamese historical monument and domestic object with the complex dilemma of memory in a society suffering immense indifference and political apathy. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s stage hangs suspended between the world of the past and the present and this suspension is integral to his art.

Interior 1 from Heritage series. 2011. Oil on canvas. 120x150cm.

Private Collection. (Fig. #2)

‘Heritage’ was begun in 2010, examining the aftermath of war through particular physical site and domestic object. These large-scale painterly interiors (see Fig. #2) were initially inspired by the palace compound of Emperor Bao Dai, Vietnam’s last king of the Nguyen Dynasty, who was also king of Annam under French protection (1926-1947). Designed and built by Robert Clement Bourgery in 1933, this compound is situated in the central highlands of Vietnam in Dalat, which was the last seat of colonial power during the Indochina period (1887-1954). Composed of three palaces or villas, this site is now a popular tourist ‘museum’ in Dalat, which is also the city where Nguyễn Thái Tuấn currently lives and works. Influenced by Art Deco design in style of architecture and idyllically situated at one of the highest vantage points of this city’s lush green countryside, the character of this site speaks to a turbulent period of Vietnamese history that is at once opulent and oppressive. Today this ‘museum’ attempts to provide a window into the life of Bao Dai’s last period in Vietnam before his self-imposed exile to France in 1949. The style of the furniture in these rooms is Western in character and the objects chosen to symbolize his reign are faded with time and are so generic in nature that it is difficult to discern the particular tastes and lifestyle of the country’s last king. Cupboards, couches, armchairs and a few token photographs above the fireplace are all that remain of this once luxurious home. What struck Nguyễn Thái Tuấn the most about this residence was his knowledge of the history of ownership, for it uniquely charts the socio-political phases of Vietnam from colonial, to imperial, to proletariat, to ‘petty’ bourgeois’, to today’s ‘new acquirers’[i] – a term coined by the artist himself denoting the burgeoning wealth of a small, yet influential, part of Vietnamese society that are ironically descendents of this historical proletariat cause. The critical poetry behind Thai Tuan’s paintings rests in his juxtaposition of differing dress and pose of social class against a near-forgotten backdrop of domestic objects that appear like a false façade. Today, this palace compound of Emperor Bao Dai’s last residency is with no public mention of its subsequent or prior owners. Perhaps this is a strategy in building national pride by eulogizing the existence of Vietnamese dynastic rule, which is ironic considering Vietnam is governed as a Communist country whose ideology opposes such a privileged class. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn deliberately alludes to such contradiction, particularly in light of Emperor Bao Dai’s palace grounds being in urgent need of maintenance, care and repair despite its popularity as a tourist site. Through his own subtle pictorial devices Nguyễn Thái Tuấn questions the effect of these changing power dynamics in ownership, prompting his viewers to remember the role of political institutions in the changes in social consciousness and cultural attitudes of society. Despite an increase in economic means in the last 20 years, Vietnamese society is still blind to the past and the physical and psychological decay of the civic, educational and cultural structures of contemporary Vietnam.

Interior 2 from Heritage series. 2011. Oil on canvas. 120x150cm.

Private Collection. (Fig. #3)

In ‘Interior 2’ (see Fig. #3), a woman wears a dress once considered typical of the ‘petty bourgeois’ that was often worn by women of North Vietnam in the 1950s. The man, with his back turned, wears the clothes of communist cadres of that time. The edges of the painting rest in gloomy light and the posture of the man adds tension to the scene, a forewarning of unfortunate things to come. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn states ‘For me, many questions arose as to their relationship in that room, asking viewers to turn to the pages of history that had recorded the class struggles between ‘proletariat’ and the ‘petty bourgeois’ from the 1950s to the years after 1975. Today, perhaps there are no more class struggles, no more education of petty bourgeois where many people died and lost their homes. A new social class emerges, of whom I call the ‘new acquirers’.’[ii] The couple in ‘Interior 3’, through their clothing and posture hints at their proletariat origins. But the opulence in the expensive furniture causes us to doubt their identity. How did they become ‘property owners’?’ Journalists and art critics abroad like to compare the development of Vietnam with China, focusing particularly on their similarity in economic reforms. Despite both societies growing ‘nouveau riche’ populations, or what Thai Tuan terms ‘new acquirers’, the acceptance of this community is particularly stigmatized in Vietnam – the creation of such wealth heavily associated with the cultural effects of colonial occupation; the trauma of a civil war that became a global Cold War battle; and a Communist agenda to modernize society in order to gain entry into a world trade economy. In contemporary life today, Thai Tuan believes wealth is far too often judged through quantity not quality, which contributes to social superficiality. The ‘new acquirers’ of contemporary Vietnam flaunt consumer brands and luxury items beside a lower class that continue to struggle with inflated costs of everyday necessity in food, fuel and rent.

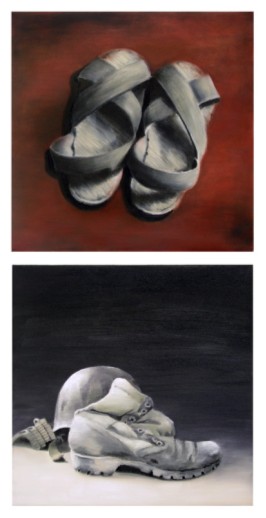

Untitled from Heritage series. 2010.

Oil on canvas. 40x40cm (each). San-Art. (Fig. #4)

In Vietnam, how the past is remembered is relegated to state-run institutions (museums, universities, libraries) that are ill equipped in funds, restricted in expertise and governed by political agenda. Within this milieu, artists are generally with little resource material from which to gain inspiration, though for Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, his exploration of the presentation of history in Vietnam offers crucial subject requiring interrogation. In ‘Untitled’ 2010 (see Fig. #4), two small paintings sit one on top of the other. The painting above depicts a pair of old and worn plastic sandals belonging to Northern soldiers of the Vietnam War. Such shoes are often found in Museums of Revolution across the country, glorifying these soldiers as heroes and are often placed ceremoniously on a piece of red velvet, encased in glass, like sacred memorabilia of great social figures. The painting below depicts a broken and torn shoe and a helmet worn by a Southern soldier during the Vietnam War. Such objects are placed in War Museums as proof of crimes committed by those who lost.[iii] The display of history in Vietnam is subtly politically motivated and the confused emptiness exuding from Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s paintings refers to the cultural and spiritual vacuum that results from this psychological control.

Untitled (The church in Quang tri) from Heritage series. 2012.

Oil on canvas. 170x200cm. Primo Marella Gallery, Milan. (Fig. #5)

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s life-long passion for the brush has offered constant solace from the dark memories that creep into his everyday; this consciousness deeply affected by the ravages of war he directly witnessed growing up in a poor village in Quang Tri Province, Vietnam between 1965 and 1975. In 1964, this southern province near the Demilitarized Zone to Northern Vietnam that runs along the bank of the Ben Hai River (which served as the geographical divide between North and South Vietnam) became a center for American bases. Four years later after the Battle of Khe Sanh, the North Vietnamese forces captured the entire area. In 1975, the country was unified under Communist rule and for the third time, his family fled and later returned to build anew, again. The suffering and pain of the local community who endured the many bombs and bullets of this traumatic period have permanent imprint on Thai Tuan’s mind and heart. In ‘Untitled’ 2012 (see Fig. #5), Nguyễn Thái Tuấn commemorates his hometown in depicting the church of his village that belonged to the South. The Northern army destroyed it in 1972 and is today considered a monument of heroic struggle. A man in military uniform stands in front of the main altar amongst a battered, bullet-marked broken edifice as beams of light filter through the outside world. This old Communist, bodiless and again with his back towards the viewer, stands bent and alone. This place that once rejoiced in faith and belief is forbidden to be rebuilt by the State and stands as a political remnant justifying the atrocities of a civil war. Thai Tuan states ‘Dostoyevsky said that ‘beauty will save the world’. For me, art has helped be a better person. A student of Hue Fine Arts College, he states ‘In those 3 years I got little out of study’ where he was taught the basics of pencil, charcoal and gouache and some graphic design that proved of use for serving the cause of propaganda. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn could be considered a self-taught painter, as he has, incredibly, never studied the language formally.

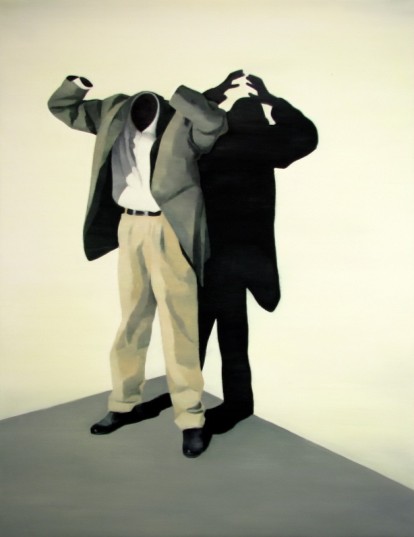

Black Painting No. 64 from “Black Painting” series. 2008.

Oil on canvas. 130x110cm. 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hongkong. (Fig. #6)

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s signature motif of the body-less figure originated in ‘Black Paintings’ 2008-2010 a series of oil paintings where the human form is given meaning by its absence. These carefully fashioned figures appear ethereal and wraithlike, their insubstantial forms mirroring the monochromatic landscape in which it is surrounded that is equally featureless and indistinguishable. In ‘Black Paintings No. 64’ 2008 (see Fig. #6), a figure clad in business attire crouches in a corner, his arms pulled taught behind his back, his headless and handless body a haunting suggestion of deformity, but more importantly a lack of individual characteristic. In another image, ‘Black Paintings No. 68’ 2008 (see Fig. #7) a body-less figure raises his arms in exasperation in an isolated room, where the silhouette on the wall reveals his missing body parts as shadow. This depiction of the body as an absence, as a shadow, is an important trait in Thai Tuan’s works where the materiality of life hides or provides a kind of frustrating camouflage for loss of identity or control. This omission of human detail, masked in a color suggesting darkness, ignorance or emptiness is a deliberate ploy by the artist. He calls into question how social systems perpetuate cultural stereotype and assumption, whether through the media, fashion, television or political propaganda. By confronting such ideas, perhaps these black forms can be transformed into a different kind of human truth. Thai Tuan comments, ‘Darkness always contains mystery and the unknown. Darkness sparks people's curiosity to step inside to find the hidden truth, but it also creates worry and turbulence.’[iv]

Black Painting No. 68 from “Black Painting” series. 2008.

Oil on canvas. 130x100cm. 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hongkong. (Fig. #7)

When asked what prompted the decision to end his ‘Black Paintings’ series which numbers in approximately 100 works, Thai Tuan states ‘The important addition … is the atmosphere of decline. I want to bring into those paintings my own perception of the society in which I’m living in, of its existence in a state of decay’.[v] Whereas ‘Black Paintings’ saw a thin use of oil in monochromatic tones where the figure was central to the image, in ‘Heritage’ there is a richer use of paint that adds lucidity and texture to scenes where the relationship between figure, object and site are carefully maneuvered under Thai Tuan’s expert use of light. Recalling the American modernist, Ed Hopper in his treatment of color in the depiction of interior spaces; while capturing a similar social darkness of Gerhard Richter who takes particular historical moments as pictorial frames and ‘iconicizes’ them; Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s current practice also recalls the contemporary photographs of American artist Thomas Demand in his stripping of time, clues and existence of people in place and also the work of Chinese artist Hu Yang, whose entry into the private spaces of differing social classes in Shanghai photographically illustrate how the ownership of objects denotes social class. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn (b. 1965) is one of Vietnam’s most significant artists of his generation, whose artistic practice is anchored in the symmetry of fullness and absence. Where are our memories fullest? What triggers/limits our imagination to recall the facts of the past? For Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, space and its objects, the relationship between body and matter, is of unquestionable import.

(Copyright: Zoe Butt, September 2012)

_________________________ [i]Email conversation between artist and author on 15 August, 2011. [ii]Ibid. [iii]Ibid. [iv]Email conversation between artist and author in 2009. [v]Ibid. [i] |