|

|

Voices of the upstream swimmers

|

|

|

(Bấm ở đây để đọc bản Việt ngữ: Tiếng nói của những người bơi ngược dòng)

Introductory comment on the exhibition Voices of Minorities

— paintings by Mỹ Lệ Thi and Nguyễn Thái Tuấn —

Chrissie Cotter Gallery, Sydney, 18/07 - 05/08/2007.

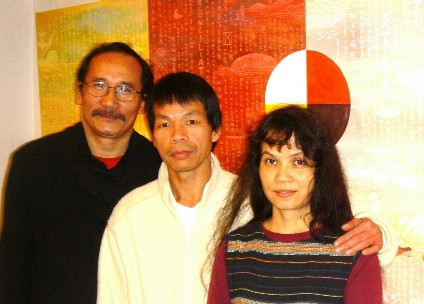

The author, with Nguyễn Thái Tuấn and Mỹ Lệ Thi

I believe that the artists as intellectuals, regardless of their skin colours and cultural backgrounds, are always the ones who choose the voices of minorities. They always keep a distance between themselves and the centres of power, between themselves and the crowds, between themselves and the well-worn paths of ideas. From these standpoints, the artists raise their voices. The exhibition Voices of Minorities introduces to us two such artists : Mỹ Lệ Thi and Nguyễn Thái Tuấn. Of course, different from socio-political activists, artists may not express their ideas directly through concrete statements. They express their ideas through creative arts, and here in this exhibition, through their paintings. Their ways of expression may produce multi-meaning effects, because their journeys may begin from unconscious impulses and be brought out in every brush-stroke on the canvas. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn has said that he paints as an unconscious reaction, without any political intentions. Mỹ Lệ Thi has also said that she paints as a reflection of her own thoughts, rather than an effort to express ‘messages’. However, from the standpoint of the spectators, we may try to make a backward journey to interpret and understand their ideas. Therefore, in this brief introduction, I will try to interpret and understand their ideas through my viewpoint. Talking about Mỹ Lệ Thi, many people often mention her minor ethnic origins. Furthermore, she is a woman. Until today, at the beginning of the 21st century, on this earth, although there may numerically be more women than men, they still form a minority! Nevertheless, I think, all these factors are not enough for us to see her as a voice of minority, because a woman of minor ethnic origins living in Australia may still imitate, or compromise the voices of the centres of power, the crowds, the well-worn paths of ideas. We can only see Mỹ Lệ Thi as a true voice of minority when, as a creative artist, she chooses the voice of minority: the voice of the mistreated, forgotten people of any skin colour, and from any geographical area. Nguyễn Thái Tuấn is a man of the Kinh people — a major ethnic group that occupies nearly 90% of the Vietnam's total population — but, as a creative artist, he also chooses the voice of minority. He paints like an exile in his own country. While a majority of his generation believe in, or hurriedly run after, the slogans issued by the centre of power, Nguyễn Thái Tuấn does not join them, but chooses to stand on the sidewalk. From his own corner, he observes life around him and, on canvas with brush in hand, creates paintings that can be seen as social criticism, paintings that are able to re-interpret, or re-define the values and standards set out by the centre of power. The very first interesting aspect of this exhibition is the meeting of the two artists. A Vietnamese woman living in exile in Australia, and a Vietnamese man living in exile in his own country, have joined to share the same space in this art gallery. And this meeting lets us see two different ways of expression — each person from her/his own minority position. While Mỹ Lệ Thi's paintings enter my senses quietly, like unceasing sounds of sutra-chanting from an inner world, I hear fitful screams echoing from the work of Nguyễn Thái Tuấn. While I may hear from Mỹ Lệ Thi's work innumerous whispering stories, I receive from Nguyễn Thái Tuấn's paintings innumerous questions that I myself have to answer.

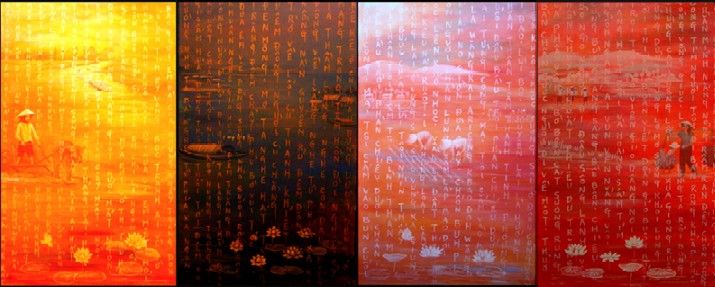

Mỹ Lệ Thi, ‘Lotus Walk’

Of course, each of Mỹ Lệ Thi's paintings does not only tell one story. In the ‘Lotus Walk’ tetralogy, for instance, I hear many stories. On the outermost layer of these four canvases, I hear the story about the four basic skin colours of humankind: yellow, black, white, red. The four skin colours, like the four seasons, float over the four landscapes of rice-fields and women labourers. This layer of four skin colours appear like an opaque veil of fog, making me recognise immediately the message that skin colours are not durable walls that separate humans from one another, but are only something very thin and ephemeral, embracing within themselves a true life of human ideas and works. Right under this layer of four skin colours, lines of words run down vertically like water streams. If we try to read these lines of words, we will hear a story telling us that an artist's labours on the canvas are as wearisome as the labours of people planting rice on the mud. These lines of words unceasingly stream from the top of the paintings; and we see, from the bottom, lotus blooms rising up, and spreading wide like a walking path. In the far distance behind this lotus walk, is a landscape of mud with labouring pesants. The story of the lotus walk brings to mind the line from a Vietnamese folkloric poem: "... near mud but does not stink of mud" — an association that suddenly brings a poetical beauty to the women bending down in the mud looking for a living. In ‘Lotus Walk’, we cannot find any compromise between Mỹ Lệ Thi and current political viewpoints of Australia today. She chooses the voice of the minority, the voice of forgotten people on the sidewalk of this contemporary industrialised life. Through this voice, she sends to us a message about equality, and reminds us of the beauties and meanings that have been subdued under infinite mechanical and urban noises.

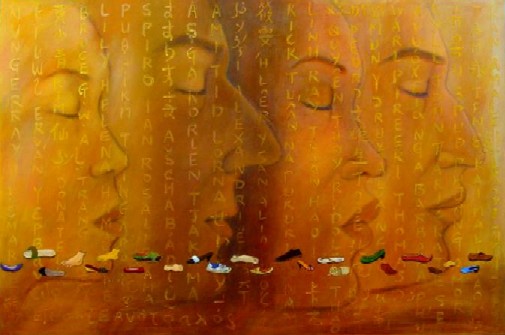

Mỹ Lệ Thi, ‘Names’

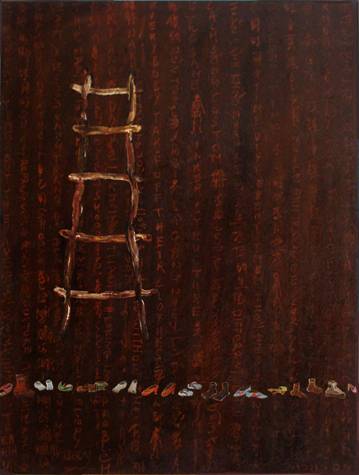

This message about equality always exists in paintings and installations by Mỹ Lệ Thi. In her painting titled ‘Names’, we see immediately on the outermost layer, a row of shoes and sandals, accompanied by bare feet, walking back and forth. Upon careful observation, we realise that they include various types of shoes and sandals from diverse peoples and classes. Then we realise that everyone, regardless of origins, are walking on the same path through life. The images of shoes and sandals with bare feet have been used in many of Mỹ Lệ Thi’s paintings as motif to create a variety of visual meanings. In ‘Names’, this motif is combined with people's names from many nations that run down vertically like water streams, and behind these names are the four human faces belonging to the four basic skin colours. In the painting ‘Transformation’, this motif is combined with a bamboo ladder, and behind it are fragments of words and miniature human figures streaming down on a gloomy, nocturnal background. While in ‘Names’ everyone has a name, a face and a pair of feet, to walk together with everyone on the path through life, in ‘Transformation’ the ladder stands solitarily like an invitation: "climb up, and transform yourselves", because with a further vision, humans will be less narrow-minded.

Mỹ Lệ Thi, ‘Transformation’

I have said that Mỹ Lệ Thi's paintings enter my senses quietly and unceasingly like the sounds of sutra-chanting from an inner world. I feel so because in her paintings there are no images especially emphasised. Every image seems to exist equally on a monochromatic, fathomless, boundless background, like the sound of sutra-chanting from Oriental pagodas, or the drone of the Australian aboriginal didgeridoo. Boundless, indeed. We feel that the lotus walk as well as the path of shoes and sandals and bare feet will extend forever, and the limit of the canvas is only a temporary physical limit. In contrast, every painting of Nguyễn Thái Tuấn's frames itself with a shadowy border, making the spectator’s view focused on the central area of the canvas, where there is light, to observe an image especially emphasised. While Mỹ Lệ Thi's paintings leave in me many quiet and prolonged impressions, Nguyễn Thái Tuấn's works throw into me many haunting screams and unanswered matters. All his paintings are untitled. The spectator is not offered any suggestion for meaning. I think it is best we should come to his works with questions.

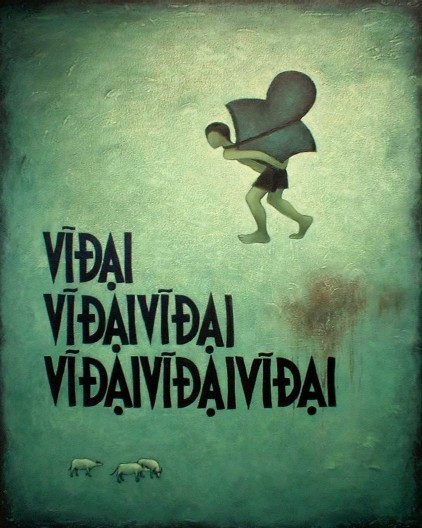

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, ‘Untitled’ No. 41

The painting ‘Untitled’ No. 41 (2005), with its grey-blue background and somber cold light, emphasises the image of a faceless mother lulling an egg. Nearby are miniature images of boys bending their backs to carry the busts of somebody, and a boat on a river bank. Why is the mother lulling an egg? Why does she have no face? Is the egg meant to relate to the legend of Âu Cơ and her hundred eggs? Why is there only an egg? Is the faceless mother nurturing her hope for another generation? Who are the boys that are bending their backs to carry the busts? Are they her lost sons? Whose busts are they carrying? What are the meanings of the river and the boat? Is that the river that had once divided the country, or the departure place of people who went into exile?

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, ‘Untitled’ No. 6

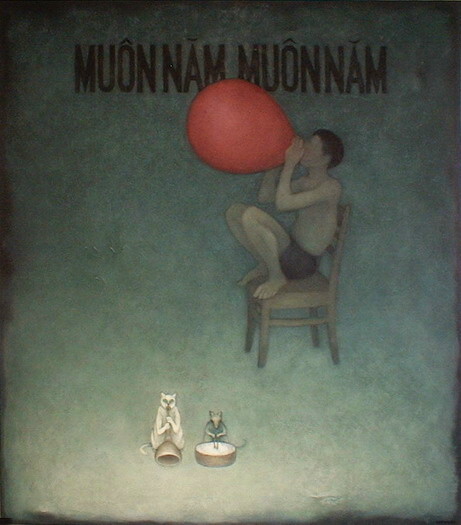

Two years earlier, the image of the boy bending his back to carry a bust appeared in the ‘Untitled’ No. 6 (2003), and perhaps that painting helps us answer some of the questions above. In that painting, the emphasised point is the large-sized word VĨ ĐẠI (GREAT) repeated six times and combined with the image of a faceless boy bending his back to carry a bust. The background has a pale-green leave colour of rice seedling fields in Vietnam, and at the left corner below it are miniature images of some buffaloes grazing leisurely. What is the real meaning of the word VĨ ĐẠI in this context? Is there any connection between the word VĨ ĐẠI and the bust sitting on the boy's curved back? The word VĨ ĐẠI is exclusively used to describe the only political leader in Vietnam, is it not? Other questions would be ironic ones that I need not write down. Similarly, in the ‘Untitled’ No. 33 (2005), we see the large-sized word MUÔN NĂM (FOREVER), repeating itself on top of a faceless boy who is sitting with his head bent upward blowing up a big red balloon near the point of bursting, and below him is a mouse and a cat playing funeral music. Is there any connection between the word MUÔN NĂM and the nearly bursting red balloon? What does the red colour of the balloon symbolise? The balloon blower is a faceless boy — why? Is there any connection between the nearly bursting red balloon and the funeral music? Etcetera. So many other questions would naturally pop up in the spectator's mind.

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, ‘Untitled’ No. 33

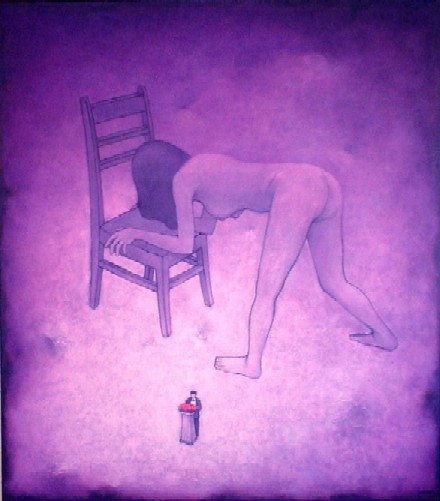

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn is a male artist, but his ‘Untitled’ No. 44 (2006) is the voice of women under a patriarchal chauvinist regime. On an erotic purple-pink background, the emphasised image is a naked woman, bending down on a chair. Below this, is a miniature image of a man solemnly delivering a speech. This striking contrast causes many dramatic questions to pop up. Is the naked woman bending down like a child waiting to be smacked? Or is she waiting for some sexual acts? What is the man solemnly declaring in his speech? Again so many questions.

Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, ‘Untitled’ No. 44

Due to the limitations of a brief introduction, I can only give a sketchy interpretation of a few paintings by Mỹ Lệ Thi and Nguyễn Thái Tuấn. What I want to emphasise is that the realistic images in their paintings are not the images that they — and we — could see through ordinary eyes, but are images that can only be seen through the eyes of contemplation. This means that, in order to see such images, the artists have to choose exact standpoints from which to observe life. Such standpoints belong to the minorities, and only from which they may see, hear and express the voices of the minorities. We often hear that artists who act as intellectuals are upstream swimmers. Choosing the voices of the minorities is itself an act of upstream swimming. To do it, Mỹ Lệ Thi and Nguyễn Thái Tuấn not only see, hear and express the voices of the minorities, but must also live with the minorities that they choose. I would like to repeat this sentence by the comedian W.C. Fields: "Remember, a dead fish can float downstream, but it takes a live one to swim upstream."

|